To develop taste, first understand deeply

Or why I started building an AI assistant and publishing my notes.

When tech journalist Robert Cringely asked Steve Jobs how he knew what the right direction for technological innovation was, Steve Jobs said:

Ultimately, it comes down to taste. It comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done and then try to bring those things into what you're doing.

Picasso had a saying. He said, “Good artists copy. Great artists steal.” And we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas. And I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world. But if it hadn’t been for computer science, these people would have all been doing amazing things in life in other fields. And they brought with them, we all bought to this effort, a very liberal arts air, a very liberal arts attitude that we wanted to pull in the best that we saw in these other fields into this field. And I don’t think you get that if you’re very narrow.

For years, I approached developing taste backward. I want to create more aesthetically pleasing visuals, design innovative and useful interfaces, and write essays with more depth. Misled by (or misinterpreting) Steve Job’s mesmerizing answer, I thought I needed to start with how I dress, how I decorate my house, how I go about my hobbies—essentially how I do all the things in my life, outside of what I was working on. Then I realized that observing, caring about, and being intentional about everything, especially the small details, is secondary.

There is a pre-requisite: to understand deeply what I am working on.

Much more than just a style of doing, good taste is a measure of a person’s intuitive understanding of a problem space.—Callum Flack

When mathematicians describe a proof as beautiful, I doubt it has anything to do with the author’s fashion or penmanship. They recognize something deeper: the proof is simple, avoids unnecessary steps, takes a clever approach, or has a pleasing logical flow. Or more likely, all of the above. Without a deep understanding of mathematics, one cannot produce such a proof. Without a deep understanding of mathematics, one will not have taste in mathematics.

This is the same in areas that are wildly different, say, swimming. I have trained for triathlons for 15 years under various coaches and competitive swimmers.1 There are swim sets that I find beautiful not because they were easy—often they were the hardest—but because they pushed me in certain ways that felt right, and they have patterns that made the mundane act of swimming up and down the 25-meter pool, watching the black line at the bottom, enjoyable. There are also terrible, ugly swim sets. I remember one I created at the University of Warwick about a decade ago. This swim set included too many laps of backstroke in the warmup to the point that most teammates were frustrated and bored. Without swimming enough, one cannot craft elegant swim sets. Without swimming enough, one will not have taste in swimming. I can know the Olympic champions and their world record timings yet not appreciate the smoothness of a swim stroke.

Matt D. Smith, the creator of an online interface design course Shift Nudge, recently wrote in an email:

Most designers hit a wall—not because they lack creativity, but because they haven’t mastered the fundamentals. When you truly understand typography, layout, and color, you can confidently break the rules without breaking the design.”

Without mastering the fundamentals of design, one will not have taste in design.

I recently came across a technical article on Cursor’s blog, Iterating with Shadow Workspaces. I barely understood 10%—or even 5%—of what Arvid Lunnemark wrote. But it is an inspiring example of someone who has thought deeply about a problem he cares about, experimented with solutions, and put his learnings into words. I don’t know Arvid but I am confident he has great taste in the problem he is tackling: AI coding.

“Intolerance for ugliness is not in itself enough. You have to understand a field well before you develop a good nose for what needs fixing. You have to do your homework. But as you become expert in a field, you'll start to hear little voices saying, What a hack! There must be a better way. Don't ignore those voices. Cultivate them. The recipe for great work is: very exacting taste, plus the ability to gratify it.”—Paul Graham

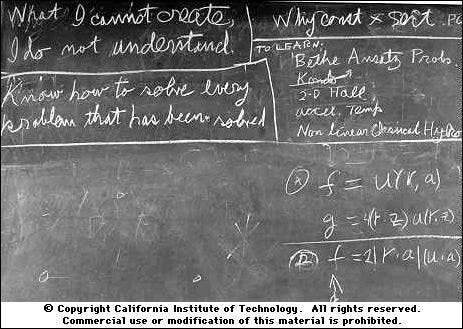

In the top-left corner of his blackboard at Caltech, alongside equations and diagrams, Richard Feynman wrote, “What I cannot create, I do not understand.” He believed that if he could not reconstruct concepts from foundational principles, he didn’t truly comprehend them.

Reflecting on my own journey, I realized that even though I have launched multiple AI products, I still don’t understand AI enough.2 That is likely why I struggle to create intuitive interfaces for AI products and write thoughtful reflections on AI. This realization drove me to build an AI assistant, prototype different interactions, and share my learnings publicly.

What I cannot create, I do not understand.

When I was learning to code about 12 years ago, I watched YouTube tutorials and replicated exactly what the developer did. Despite multiple attempts, I couldn’t get over the initial learning curve to be comfortable with coding. Over the next few years, I learned there are two more levels of learning, which require more involvement:

The first level I was on is rather passive. I don’t do much thinking; I just follow. I tend to start here for topics I have almost no knowledge about, such as building a GPT.

For the second level, I still follow tutorials but I make some modifications, even minor ones, to force myself to think and solve similar problems. For example, I watched Lee Robinson’s videos to build my personal site.

The third level requires me to be well-equipped enough. I attempt to build something different using what I have learned to check that I understood what I learned. I also avoid using frameworks when I’m practicing because the abstractions prevent me from learning about the underlying functions.3

Sometimes, the problem space is much bigger than the technical aspects. To create a successful product, I also have to understand our target customers. They are also a part of our problem space. No startups build products to solve everyone’s problems. Who are we building for? What do they care about? How do we reach them? What resonates with them? Some entrepreneurs shortcut this learning step by choosing to solve their own problems because they already know themselves well.

“Taste is cultivated by a natural curiousity for a problem space. Because one find it fun, it becomes easy to spend deep focus honing one’s attention and skills within the space, squishing knowhow into smaller and smaller bundles in order to discover more and more interesting things within it.”—Callum Flack

I’m only a month into my AI learning journey. I will admit my taste needle has barely nudged, and I harbor no illusions about developing refined taste so quickly. But I’m beginning to feel a little less lost in my conversations with my technical cofounder SK and my suggestions are becoming more substantive. I started to not only think about what we are working on now but also what we should consider next. I can also appreciate OpenAI’s Operator design and have opinions about it. These are little things but feel like baby steps in the right direction.

Instead of just treading water to keep myself afloat, I’m learning to swim.

I won’t say I have great taste in swimming but my taste in swimming is definitely better than my taste in mathematics.

While I don’t think it’s necessary to know how to train a model from scratch to design interfaces or write essays on AI, I believe the knowledge allows one to appreciate the technical aspects more, which will influence design and writing.

Of course, a certain level of abstraction is necessary. For what I hope to learn, typing binary codes isn’t useful.

I enjoyed reading this Alfred

Understanding, to me, can feel difficult because it requires sustained attention and a willingness to throw away mental models that don't fit anymore. Doing both of those things take work.

It's a "cognitive load" that feels like pain but probably is just your brain adjusting to what is new.

But it can be gratifying I think. Maybe like the strain your muscles experience when you go to the gym.